Conspiracy weary

Illuminati, Qanon, anti-vaxxers... why are we still so willing to put our trust in utter nonsense?

There’s a small Dutch town in the south, called Bodegraven-Reeiwijk. It was home to several Golden Age painters, and is otherwise unremarkable. Visitors can enjoy the Gouda Cheese Experience, boating on the Oude Rijn river, and a pleasant nature reserve and lake rated ‘excellent’ on Google.

If you look it up on Wikipedia, however, its page contents read: ‘Population centres, Topography, Paedophilia rumours.’ Back in 2020, several claims were made online that the town was home to satan-worshipping paedophiles in the ‘80s, and the chief rumour-instigator insisted he had witnessed this personally.

Over the past two years, a steady trickle of mourners has arrived at the town’s cemetery to leave flowers on the graves of random children who were allegedly killed by this cult.

The town swiftly gathered its forces and took the issue to court, blaming Twitter for perpetuating false claims, hurting the families of the deceased and imposing a falsified notoriety on the innocent town. This week, the ruling came that Twitter had ‘done enough’ to remove the offending posts and that some claims couldn’t be easily traced. The three men behind the rumours are now in jail for making death threats.

For the 35 000 residents of the town, however, their bucolic location may now always be associated with the false allegations - regardless of whether they ever had any basis in fact.

Are you reading this thinking, “well, maybe it was true. How do they know? Of course the establishment would try to shut down rumours. That’s what they do, isn’t it”? Then congrats, you’re already a conspiracy theorist.

In 2022, certain members of Qanon believe that Trump warned of the Queen’s death

“Asking questions”, “thinking for myself”, “refusing to believe what we’re told” - all are the proud claims of conspiracists throughout history. In ancient Rome, an angry rumour spread that Emperor Nero had left the city, already knowing Rome would burn to the ground. In 2022, certain members of Qanon believe that Trump warned of the Queen’s death in a carefully coded message, delivered weeks earlier.

What differentiates thoughtful analysis and assessment of claims from conspiracy theory is that the latter rejects all evidence to the contrary. The rule of law is a lie, the pronouncements of all politicians are the bleating of establishment shills, the findings of science are funded by Big Pharma and everything else is a plot concocted by the Deep State, a non-existent entity conjured by Trump to explain why his popularity was waning. Or was it - because how would we know if it really existed?

In a world where everyone has a voice, any orthodoxy can be challenged. You simply need enough followers to sow your seeds of doubt far and wide.

This week, in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian, perhaps the weather event that sounds most like a call centre manager, Lauren Witzke, a QAnon-supporter and 2020 Republican candidate for Delaware (she got 2% of the vote) remarked that she has no doubt “technology exists to manipulate weather”. She believes that the hurricane was created to target Ron DeSantis, governor of Florida and wasted no time in whipping up her supporters with her keen grasp of scientific facts.

“We know the technology does exist,” she said. “Of course they would be willing to do something like this to target red states. I have no doubt…I know Florida is prone to hurricanes,” she added, reasonably. “However this developed to [a category 5 storm] overnight, and it does seem to be hitting the conservative areas.” She theorised that it was ‘punishment’ for the Governor’s’ ending of vaccine requirements.

Her comments were an almost perfect conspiracy storm - Qanon, dangerous science, malevolent Democrats and anti-vaxx rhetoric.

In the US, always a hotbed of conspiracy theorists from the moon landings to Roswell to Marilyn to Kennedy’s death, the FBI recently warned that movements such as Qanon are ‘likely’ to create the motivation for violent acts in the real world. Ya think?

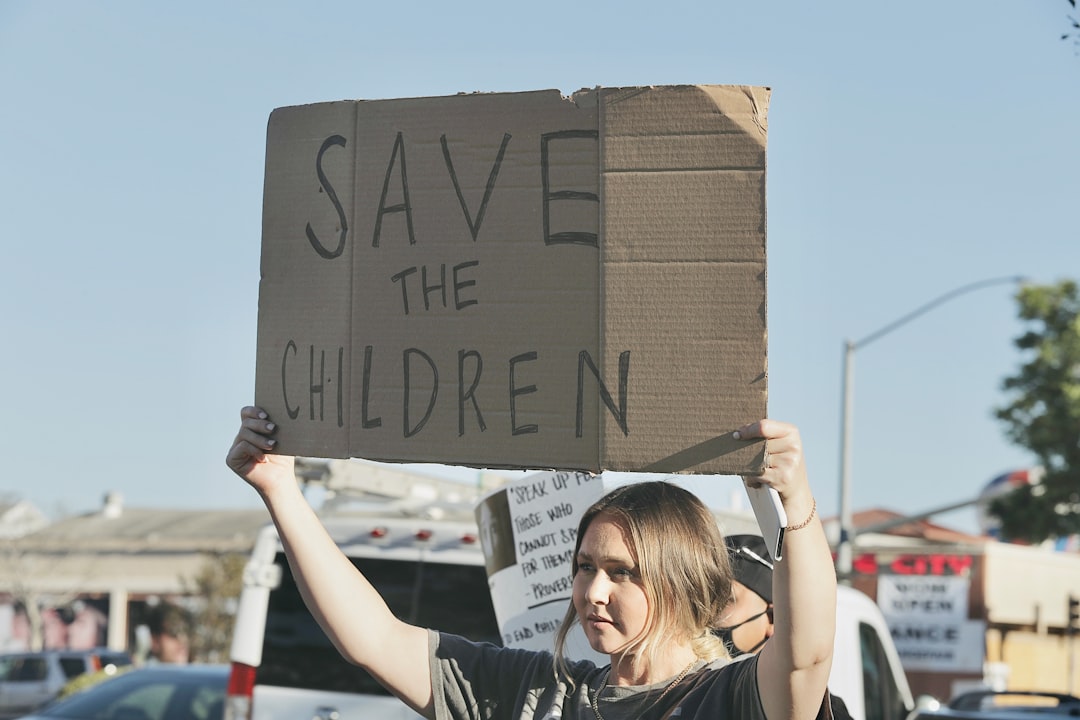

The collective - some would say cult, though it exists largely online - is rooted in the evidence-free belief that the world is run by satan-worshippers who sex-traffic children. Trump’s presidency crystallised believers into an unshakeable certainty that he was cleverly and subtly undermining this evil cabal, and that soon would come the day of judgement when he would reveal the key players and bring down the vast global conspiracy.

‘A group of Satan-worshiping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media’

Hilarious, obviously. Yet a poll last December by NPR and IPSOS found that 17% of Americans firmly believe that “a group of satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media”.

That’s millions of people, sitting around the backyard barbecue, driving to their normal jobs, picking up string cheese at Walmart, thinking “Hillary Clinton is a child sex trafficker and she’s worshipping satan with Bill Gates.”

How do we know she’s not? We don’t, other than the fact that there’s zero evidence to suggest it’s true. But evidence doesn’t matter, once an internet rumour has traction.

For all anyone knew, Q was a 13 year old in his bedroom

Qanon has only been going for five years, sprung from an anonymous post on the famously incel-friendly site 4chan, from one ‘Q Clearance Patriot’, who claimed to be a high-level government insider, and predicted ‘the Storm’, or the moment of Trump’s revelatory triumph. It’s almost as if Nazi imagery was involved.

For all anyone knew, Q was a 13 year old kid in his bedroom in Buttville, Idaho. No matter. Trump’s passionate supporters loved the idea, they wanted to connect with people who felt vindicated by the coming Storm, too - and a global conspiracy was born.

Only in America, of course, home of the passport-free, basement-dwelling, Youtube-gulping, gun-toting, nut-job whack-a-doodle. Except it’s not only there - because Britons are increasingly willing to embrace conspiracy theories too, in the guise of “thinking for myself.”

From relatively stupid-but-apparently-harmless accusations of celebrity and establishment lies - “The Queen actually died years ago”, “She was never pregnant, it was a surrogate”, “She’s a paid actor”, “He’s totally gay” - to a fundamental conviction that we’re living in a state-sponsored simulation and the Illuminati are coming for our children, the range of theoretical beliefs in completely unproven and unlikely claims is alarmingly high.

28% think the world is run by a secret group of people

A survey in January 2021 found that in Britain, 12% believe the US government was involved in the 9/11 attacks, 12% think the harmful effects of vaccines are hidden from the public, 28% think the world is run by a secret group of people, 9% believe that climate change is a hoax and 20% of British adults believe that humanity has made secret contact with aliens.

Of course, we have to hope there’s significant crossover amongst these daydream believers, and reassuringly, it’s also the case that people in Britain are globally less likely to believe conspiracy theories than other nations, bar Japan and Denmark.

That still leaves 14% of us fully paid up members of the Think For Yourself club, however. And most damaging, of late, have been the many Covid conspiracy theories, fuelled relentlessly by social media.

The most dangerous virus the world has known, which was killing millions and whose spread was running so unchecked that it was necessary to lock down entire continents to prevent a tsunami of death, was considered by a significant number of people not to exist at all.

It was a ‘plan-demic’, or ‘scam-demic’, designed to keep us locked up while the world’s governments went about their evil business. Or perhaps it was real, but created by the Establishment to kill off the weak and sick.

Some believed the vaccine was in fact the wicked plan of Bill Gates

When scientists produced a vaccine, having taken many months to study the virus and synthesise an antidote, and tested it comprehensively because endless funding was unprecedentedly available to do so, Jade from Rhyl on Instagram with several thousand followers for her wellbeing salon wasn’t sure about having it because ‘they’d developed it too fast.’ She’d rather ‘take her chances’ as most people didn’t seem to be very ill, and it was just like a cold, or that’s what she’d heard off her friend whose cousin got it.

Some believed the vaccine was in fact the wicked plan of Bill Gates (tireless star of many conspiracy theories), implanting microchips in our blood to track us, and the sheeple eagerly queuing with rolled sleeves would soon become drooling zombies.

In March 2020, the hashtag #FilmYourHospital was trending in the US, on the basis that rather than the expected surge of admissions, the hospitals were empty and it was all a cunning hoax. There was no explanation as to why hundreds of governments would band together and create fake film sets featuring people dying horribly and doctors weeping, involving a cast of thousands and the bought silence of many more, but enough people believed the faked footage to have their faith in medial science shaken.

A later study found “the oxygen that fuelled this conspiracy in its early days came from a handful of prominent conservative politicians and far right political activists on Twitter.”

Finding their Libertarian principles threatened, their answer to lockdown was to deny the truth of what was happening.

Such denial spread quickly to the UK, too A study found that certain political and social beliefs were strongly affiliated with different conspiracy theories around Covid and the vaccine. Right-wing authoritarians who distrust scientists tend to believe that the virus was created in a lab, but the 5G conspiracy theory (what? Oh, the roll-out of better mobile signal somehow created a virus and nobody would admit it) - is associated strongly with a distrust of ‘straight science’ but not ring-wingers (perhaps because there’s money in 5G).

“So what?” You may say. “People are entitled to their beliefs.”

Meanwhile, those convinced it originated from a bat in a meat market are typified by “intolerance of uncertainty, ethnocentrism, (and) COVID-19 anxiety,” but those people also tend to believe scientists.

“So what?” You may say. “People are entitled to their beliefs.” But the same study also found that belief in Covid conspiracy theories is associated with “negative public health behaviours such as unwillingness to social distance and vaccinate against the virus.”

According to a recent comprehensive study from the University of Sheffield,

“Conspiracy theories are unsubstantiated explanations of major events with a twist - that powerful and malevolent actors are involved in secret plots for their own benefit to the detriment of the common good.”

They involve complexity and secretive behaviour, and vitally, “function to protect entrenched beliefs by discounting contrary evidence as the product of a conspiracy.”

Unsurprisingly, belief in one conspiracy theory tends to predict further belief in others

Unsurprisingly, belief in one conspiracy theory tends to predict further belief in others - so if you think Princess Diana was murdered, you’re more likely to assume the US government are communicating with aliens and Covid is a plan-demic.

But while the non-conspiracists among us might rail at the stubborn insistence of the conspiracists that the vaccine is causing thousands of deaths, or that it’s better to risk polio than inject your child with ‘stuff we don’t understand’ - (maybe that’s because we’re not medical scientists who’ve spent years working on preventing fatal childhood diseases) - it’s helpful to understand what drives these unshakeable certainties.

People are more likely to turn to conspiracy theories when uncertainty and stress are high

According to the authors of the Sheffield University study, “conspiracy thinking may ... confer a sense of control during periods of perceived uncertainty or threat.”

Further research has shown that people are more likely to turn to conspiracy theories when uncertainty and stress are high, and those who struggle to tolerate uncertainty show a “tendency to seek simplifying explanations, often involving external and threatening agents.”

‘Authoritarian’ personalities are also more likely to engage with conspiracy theories, due to anxiety and “difficulty with higher-order thinking” - basically, the more rigid your outlook, the less able you are to navigate ‘not knowing’, and the more likely to seek an all-encompassing explanation for nuanced and complex difficulties.

The Education and Training Foundation (ETF) has also looked into the reasons why people are likely to believe in conspiracy theories and adds, “those who are attracted to conspiracy theories generally feel insecure in their everyday lives and are trying to find order in a disordered world. This has particularly been the case over the last two years with the Covid outbreak, but now with the invasion of Ukraine, life has become even more uncertain.”

They also acknowledge that for some at least, there’s a huge entertainment value. In the same way we enjoy gossip about celebrities, the addition of secrets, mystery and the chance to ‘do your own research’ and uncover supposedly hidden facts and patterns is compelling.

It’s the Famous Five but with sex trafficking and zombies

“Much like a scary movie or detective novel, conspiracy theories typically involve spectacular narratives that include mystery, suspected danger, and unknown forces that are not fully comprehended,” says the authors of the Sheffield study.

Effectively, it’s the Famous Five but with sex trafficking and zombies. For generations whose world view has been shaped by populist TV thrillers and video games - both of which provide a mystery which is then solved by dogged perseverance against the odds, and more often than not, features an authority figure brought low- its not surprising that so many enjoy the sense of a game; pitting their wits, the little guy, or girl, against the faceless corporation.

The internet has brought those people together - and now, endless chat forums and social media sites allow them to reinforce one another’s wildest theories.

“Conspiracy beliefs are associated with decreased analytic thinking, and an increased reliance on one’s emotions and intuitions,” say the authors of the Sheffield study.

“Belief in conspiracy theories is also associated with feeling unique and special, an inflated evaluation of the self (i.e., narcissism) and an inflated evaluation of the groups that are central to a perceiver’s identity (i.e., collective narcissism.”

Other studies have found that people are more likely to believe in scientific facts if their friends appear to do so - and so the converse is also true. The more online content people are exposed to which casts doubt on vaccines, or government information, the more likely they are to invest emotionally in conspiracy theories.

‘Biden Builds Transhuman Cyborg Army Using Immigrants’

Social media AI algorithms exploit this deeply human tendency by recognising what you’ve clicked on and providing more extreme versions of the same, which is why it’s easy to go from ‘perhaps the government doesn’t always tell the truth’ to ‘Biden Builds Transhuman Cyborg Army Using Immigrants’ - a genuine headline on a far-right US site. And then you don’t know what to believe.

Of course, governments do lie, the famous are revealed to be sex offenders, and science can go wrong. But on most occasions, in most situations, Occam’s razor - the theory that ‘the simplest of competing theories be preferred to the more complex’ - is the sensible assumption.

Yet it’s more reassuring for many to believe that the world is run by people who know what they’re doing and have a grand plan we can expose and derail with our swords of truth, than it is to accept the lonely reality - that most people, at every level, are just being human, with all the chaos it entails, and that rather than living in a masterful simulacrum run by lizard overlords, we are all simply “swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight/Where ignorant armies clash by night,” to quote Matthew Arnold.

‘Think for yourself’ say the T shirts and hashtags. By all means - and then defer to someone who knows more about it than you do.

KEEP READING…

LOCHED UP: MY LIFE IN RURAL SCOTLAND

This week, everything’s gone green. Unfortunately.

I may have mentioned that we live in a small, one-storey, two-bedroom cottage in the middle of nowhere. Beside the loch, beneath the trees, forest at the back and 26 miles of water at the front. Because of this, decorating our house is extremely important to me, because aside from nature, there’s literally nothing else to look at.

Andy lived here for many years before me, in what I prefer to call ‘the ascetic monk phase’ of his life. Like Leonard Cohen in his sparse room on Hydra, Andy’s preference was for stark white walls, minimal furnishings, a small bucket of firewood and a guitar in the corner. However, Andy is not a millionaire genius musician who can get away with it indefinitely.

Hence, when I moved in, back in 2016, I brought a great deal of stuff with me, including many crates of books, two cats, a mirrored 1950s cocktail cabinet, an enormous amount of clothes, several large, framed pictures, and more mirrors than a Versailles fairground.

‘The old woman who lived in a shoe’s bring and buy sale’

To his credit, Andy accommodated and assimilated these things, and if he felt any distress as his home transformed from ‘Buddhist meditation cell’ to ‘the old woman who lived in a shoe’s bring and buy sale’, he was kind enough not to say much.

It took me four long years, however, to break him on wall colour. Eventually he gave in, as long as I did all the painting and he didn’t have to be involved.

During the first lockdown, I painted the living room black, the spare room mushroom brown and the kitchen pale green. I’d already persuaded him that the bedroom needed to be painted Arsenic by Farrow & Ball.

My decorating choices are largely ‘inter-war opium den’. If there’s a lacquered scarlet parasol and a stuffed parrot, I’m instantly at ease. I like dark colours, draped silks, jewel-toned velvets, piles of books and embroidered cushions, Art Deco mirrors and the sort of furnishings you’d find in a Shanghai brothel in 1932.

So, after a summer of moaning about how horrible our bathroom is (Andy painted it a serviceable blue 25 years ago, and it’s like bathing in an Antarctic research station), I decided it was time.

I had a vision, based loosely on my half-formed idea of a colonial outpost in Malaya in 1923. ‘Jungle, but chic’, I decided. I ordered very expensive dark green paint ‘with a black undertone’ (“Not black AGAIN” Andy said) and a very expensive cream paint for the dated tongue and groove woodwork.

I have weird associations between famous people and bits of rooms

I also bought a small, repro wooden corner cupboard to replace the ‘90s basic beech, mirrored bathroom cabinet (“er that was very expensive, in fact, and its got room for everything”) and then I covered the room in plastic sheets like a serial killer and washed down the walls and sanded the woodwork while I listened to Desert Island Discs. I only ever listen to it when I’m painting, so now I have weird associations between famous people and bits of rooms. Damien Lewis - that tricky bit round the kitchen cupboard. Melanie C- the window frames in the bedroom.

It took me the whole of Saturday. My fingers seized into an arthritic claw from sanding, and my thumb developed a blister from painting. Obviously, I want to say, “and tah-dah!” but, as it turned out, 2.5 litres is not enough for a medium sized bathroom that needs four coats.

I got through Kate Moss, Adele, Stephen Graham, Jay Blades (very moving) and a very interesting Saville row tailor from Trinidad, then the paint ran out, leaving patches the colour of Fungus the Bogeyman’s jacket and a streaky bit above the bath.

Now, all my beauty crap is in the hall, Andy keeps going in the plastic-sheathed bathroom and saying, “what sick, twisted individual did this?” in a Taggart voice, and I’m covered in green splashes. The next tin of expensive paint we can’t afford won’t arrive till next week, and frankly, I wish I’d never started.

Except for the fact that I have to prove Andy wrong, and realise my decorative vision where Apocalpyse Now meets White Mischief. Sadly, at the moment, we’re stuck in Apocalypse for at least another week.

KEEP READING…

RECIPE OF THE WEEK: FABULOUS FISH PIE

The useful thing about this pie is that you can use whatever fish you happen to have in, as long as it’s not very oily (sardine pie isn’t great). It’s a bit of faff, but nothing you can’t do while scrolling Twitter with one hand. The main thing is, make sure you cook enough potatoes to cover the whole top or you’ll have a weak and imbalanced, leaky pie and nobody wants that. It’s a deeply satisfying tea on a cold Autumn night and if you use frozen fish and prawns, it shouldn’t be obscenely expensive either.

Better still, you don’t have to stick too rigidly to the recipe, and it will still work out.

Serves 2 fairly greedy people

Ingredients

5 or 6 medium sized Maris Piper potatoes (or similar)

a knob of butter

2 cod fillets

2 salmon fillets

12 large prawns

1 tbsp butter

1 tbsp flour

400g milk

a few stalks of parsley

1 bay leaf

1/2 small onion

a handful of frozen peas

salt and pepper

a handful of grated cheddar

Method

1 Peel and halve your potatoes, add to a large pan of cold, salted water and set them to boil. When they’re cooked through, drain and mash with butter, salt and pepper, then set aside. (I use a potato ricer - life changing for lump-haters.)

2 Add the milk to a shallow pan, along with the bay leaf, parsley, onion and fish fillets. Simmer until the fish is cooked through, then drain the milk into a jug, discard the herbs and onion and cut the fish into cubes.

4 Add the butter to a small saucepan, let it melt, then briskly stir in the flour to make a roux. Add the milk, whisking, and bring almost to the boil (keep whisking) until the sauce thickens.

5 Heat the oven to 180°C (160°C fan) and cook the prawns in a frying pan if raw. (You don’t want the prawns to get cold, so only do this when you’re almost ready to assemble the pie.)

6 Add the fish, prawns and peas to a 1 litre pie dish, season with salt and pepper and pour over the sauce. Using a fork and spoon, apply mashed potato to the top (go round the edge first, it makes it easier to fill in the centre.) Rough the top up with the fork to create little grooves.

7 Sprinkle the cheese over the top, then bake for 40 minutes or until the cheese has melted and the potato is crisp on top.

Thanks for reading Decommissioned. I really appreciate it. If you like it, please do share it - and subscribe, leave comments, you know the drill. In your inbox every Thursday.